I have a “wish list’ of charities I’d like to support if I ever won the lottery. Do you? What kinds of causes do you like to support? I’m gearing up to host a fund-raising event (on Facebook) for a friend who is on the national kidney transplant waiting list (more about that later), and it made me think about subscriptions and charitable associations and fund-raising events the way they worked in the Regency. The concept of computers, the Internet, and a place called Facebook where people from all over the country –the world– could gather “virtually” for a pretend party would really blow the mind of someone from our favorite era!

I have a “wish list’ of charities I’d like to support if I ever won the lottery. Do you? What kinds of causes do you like to support? I’m gearing up to host a fund-raising event (on Facebook) for a friend who is on the national kidney transplant waiting list (more about that later), and it made me think about subscriptions and charitable associations and fund-raising events the way they worked in the Regency. The concept of computers, the Internet, and a place called Facebook where people from all over the country –the world– could gather “virtually” for a pretend party would really blow the mind of someone from our favorite era!

Naturally, as soon as I started to delve into this topic, I realized how huge it was. So many different threads, so much information. Where even to start the conversation? So I thought about our stories, the ones we love to read and write. How often have you read (or written) characters who were engaged in supporting or championing some charitable cause? Have you come across, or written, characters who are attending events for charity as part of their London season? Or attending meetings of a philanthropical association? I certainly have read books where this is the case, but I don’t feel as though I see it often.

I think in very general terms modern society has shifted away from the kind of “giving” mindset that prevailed in Regency times, and that philanthropy is not as fundamental to our daily lives as it was then. We have higher expectations of what our tax dollars should accomplish through the government, we have “lost the religious underpinnings of society”, as one scholar put it, that helped make charity a priority, and we have a society now where a majority of women work at jobs outside the home, which robs them of the time to be actively involved in charitable works. Does that make it harder for us to imagine a world where this was not the case?

I’m talking in broad generalities, of course. But in the Regency, supporting charitable causes was much more personal, more “hands-on”, if you will. The mail was too expensive to be used to send out appeals, and of course there weren’t any telemarketers badgering people to give. (Hmm, think of that!) But there were a variety of other ways one’s generosity would be solicited.

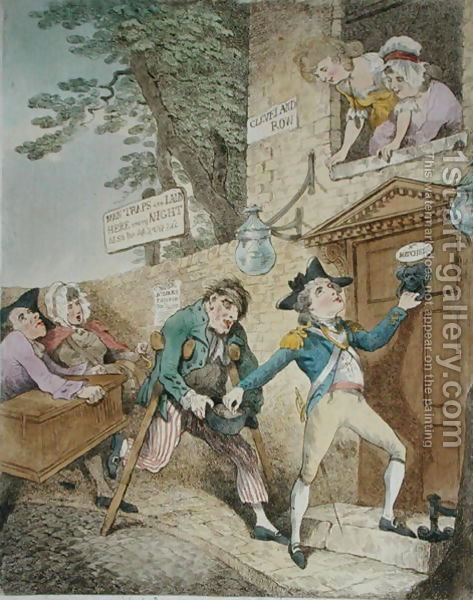

Your local church (or I assume, the synagogues as well) would present you with causes and solicit your support. I’ve been reading Woodforde’s Diary of a Country Parson and was impressed, as he was, by the generosity of even his poor parishioners who dutifully would contribute pence whenever he put forward a need during the Sunday sermon. You might be accosted on the streets by beggars, although by the Regency there were more institutions in place to help or relocate them. And of course, your friends might beg you to support whatever cause had caught their attention, through a subscription or attendance at an event. (Getting back onto more familiar ground!)

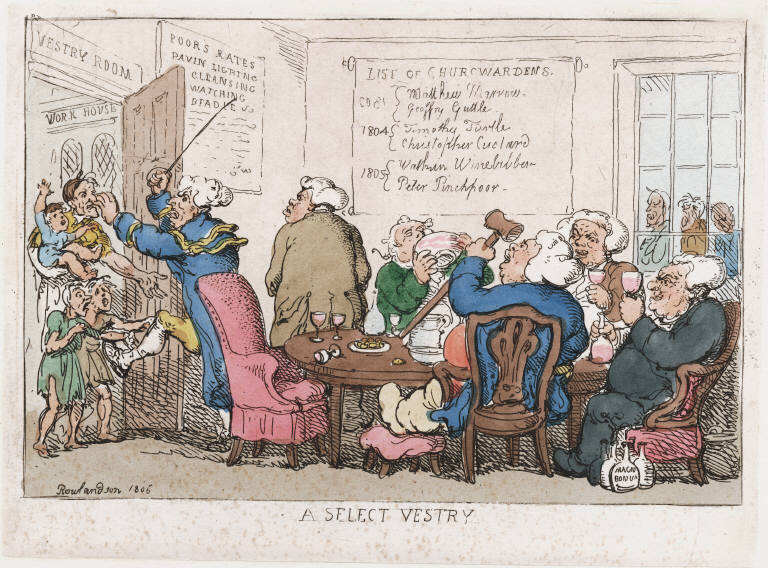

Besides these types of what is called “casual charity”, there was organized giving. This includes giving of alms, paying the poor rate tax (set up by the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, administered by the parishes and based on land and buildings, it funded the workhouses –“indoor charity”—and “outdoor charity” such as the dole, clothing, and food, among other things), or supporting any number of philanthropic organizations and associations. Bequest charities administered by parishes and guilds had a long history, but “associational charity” began to grow in the middle of the 18th century after it became illegal to establish charitable trusts through a will at death.

Besides these types of what is called “casual charity”, there was organized giving. This includes giving of alms, paying the poor rate tax (set up by the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, administered by the parishes and based on land and buildings, it funded the workhouses –“indoor charity”—and “outdoor charity” such as the dole, clothing, and food, among other things), or supporting any number of philanthropic organizations and associations. Bequest charities administered by parishes and guilds had a long history, but “associational charity” began to grow in the middle of the 18th century after it became illegal to establish charitable trusts through a will at death.

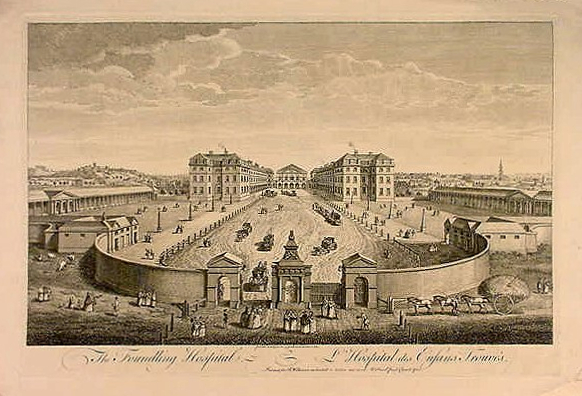

The famous Foundling Hospital was the first of these new kinds of socially active charitable foundations. The Marine Society (which placed poor adolescent boys into careers at sea), and The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes soon followed, and then many more, focused on particular social problems, and dependent on public support. Annual subscriptions, publicity campaigns through pamphleteering, and charity events including concerts and balls were all employed. Some societies levied a weekly fee on members to support their work. Medical charity took on a new approach, too, with the establishment of charity hospitals, dispensaries, and asylums. As we see so often, these changes were the beginning of a more modern way of thinking and doing, well established by the Regency period. There’s a great article here.

The famous Foundling Hospital was the first of these new kinds of socially active charitable foundations. The Marine Society (which placed poor adolescent boys into careers at sea), and The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes soon followed, and then many more, focused on particular social problems, and dependent on public support. Annual subscriptions, publicity campaigns through pamphleteering, and charity events including concerts and balls were all employed. Some societies levied a weekly fee on members to support their work. Medical charity took on a new approach, too, with the establishment of charity hospitals, dispensaries, and asylums. As we see so often, these changes were the beginning of a more modern way of thinking and doing, well established by the Regency period. There’s a great article here.

I tackled this topic because on October 30 I am hosting a “virtual” Halloween Party on Facebook, and any of you who are reading this (and are Facebook members) are invited! It’s going to run 4pm-midnight (Eastern) so you can drop in at any time. It is a fund-raising event, so I am asking people to donate $15 –or whatever amount they wish – to my friend’s fund at the Help Hope Live Foundation. (Her name is Joyce Bourque). If you would like to come to the party, you can send me a “friend” request (Gail Eastwood-Author) or drop me an email, or I think you can just find the event page I will be setting up and ask to be invited in. (I think we’re calling it “Virtual Halloween Party for Joyce Bourque’s Kidney Fund” and I hope to have it set up this weekend!) I am also going to set up a dedicated email address where non-FB folks can leave Joyce a message of support or Halloween wishes. As you may –or may not—know, people who are on transplant waiting lists are required to do fund-raising while they wait, every year. These folks have to show that they can cover their part of the cost to save their lives, or be dropped from the list. Foundations like Help Hope Live are designed to hold and manage the funds until they are needed. Here’s a link to the foundation: https://helphopelive.org and here’s a link to Joyce’s page there, if you’d like to “meet” her! If you like, you can pretend her page is a handbill that I passed to you when I stopped in for tea! J

Meanwhile, let’s chat about whether charity giving belongs in Regency romances or not. What do you think? Please comment below.